Ebola threatens chocolate

Ebola is threatening much of the world’s chocolate supply.

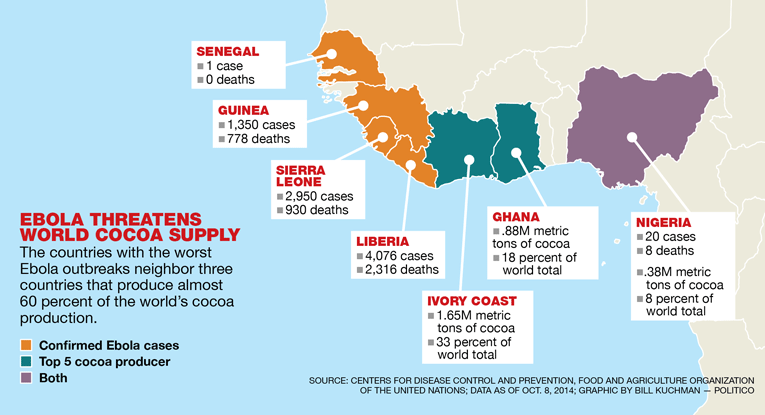

Ivory Coast, the world’s largest producer of cacao, the raw ingredient in M&M’s, Butterfingers and Snickers Bars, has shut down its borders with Liberia and Guinea, putting a major crimp on the workforce needed to pick the beans that end up in chocolate bars and other treats just as the harvest season begins. The West African nation of about 20 million — also known as Côte D’Ivoire — has yet to experience a single case of Ebola, but the outbreak already could raise prices.

The world’s chocolate makers have taken notice.

The World Cocoa Foundation is working now to collect large donations from Nestlé, Mars and many of its 113 other members for its Coca Industry Response to Ebola Initiative. The initiative hasn’t been publicly unveiled, but the WCF plans to announce details Wednesday, during its annual meeting in Copenhagen, Denmark, on how the money will fuel Red Cross and Caritas Internationalis work to help the infected and staunch Ebola’s spread.

Morristown, N.J.-based Transmar Group, an international cocoa supplier, already has pledged $100,000, and Mars has indicated its support, too.

“As a member of the WCF and a supporter of the CocoaAction strategy, Mars is pleased to see the industry coming together to help organizations on the ground in the prevention and eradication of the Ebola virus,” the company said in a statement provided to POLITICO. “We look forward to the WCF partnership meeting in Copenhagen next week where we will learn more about the industry effort.”

Ivory Coast, which produces about 1.6 million metric tons of cacao beans per year — roughly 33 percent of the world’s total, according to data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization — closed its borders in August to Guinea and Liberia. More than 8,000 have been diagnosed with Ebola, and nearly 4,000 have died in those two countries and Sierra Leone. Next to Ivory Coast is Ghana, the world’s third-largest producer of cacao beans — 879,348 metric tons per year — or 15 percent of the world’s total.

Tim McCoy, a senior adviser for the WCF, said signs that Ivory Coast residents already are concerned were immediately obvious during his last trip to the country in September.

“Going into meetings where … you always shake hands and often times, with men and women, you do the cheek kiss thing … They weren’t doing that,” McCoy said.

The market is worried, too. Prices on cocoa futures jumped from their normal trading range of $2,000 to $2,700 per ton, to as high as $3,400 in September over concerns about the spread of Ebola to Côte D’Ivoire, noted Jack Scoville, an analyst and vice president at the Chicago-based Price Futures Group. Since then, prices have yo-yoed down to $3,030 and then back to $3,155 in the past couple of weeks.

“There are still some fears out there,” he said, and he stressed new concerns that there may not be enough labor to bring in what’s expected to be another strong harvest this year. Ivory Coast farms traditionally rely on migrant workers from Guinea and Liberia to bring in the crops.

Meanwhile, Zurich, Switzerland-based Barry Callebaut — the chocolate industry’s largest player with a major presence in Ivory Coast — is reaching out to employees at its two cocoa processing plants in the country and as many farmers as it can to educate them on how to avoid getting sick and spreading the disease, according to spokesman Rafael Wermuth.

Callebaut’s state-of-the-art Cocoa Horizons truck has been trundling through the dusty back roads of the Ivory Coast for a year and half now, helping educate farmers on how to increase yields and even entertain children with cartoons played on a massive fold-out screen. But the epidemic has added such new urgency that Callebaut employees now take time out from their presentations to show the best ways to avoid contracting Ebola.

Simple precautions to avoid getting infected by the virus, which is spread through bodily fluids, are widely known in more urban settings, but Callebaut is taking the message to the remotest of rural villages. To keep yourself protected, the Mayo Clinic advises frequent hand-washing, avoiding “bush meat” because the virus can be present in wild animals, not handling corpses and limiting person-to-person contact.

Other international companies with big investments in West African cocoa production are also investing in Ebola education, too.

Nestlé, the world’s largest food company and the maker of Baby Ruth and Crunch bars, is working both in and out of the infected countries.

”We have taken measures to educate all our staff in Central and West Africa on the virus and the best ways to prevent against it whilst encouraging them to share this information with their families and communities,” a company spokeswoman said. “We are closely monitoring the situation in conjunction with the relevant authorities and following their recommendations with regards to the movement and regrouping of people. We are supporting the needy in some affected zones due to the lack of food and potable water.”

The chocolate giants don’t have to look too far for an illustration of the danger that threatens the Ivory Coast.

Callebaut doesn’t have any facilities in the three West African countries at the center of the outbreak, but the company earlier did buy beans from middlemen that acted as the go-betweens for farmers and processors, Wermuth said. That stopped recently when Callebaut lost contact with the sellers, Wermuth said.

Ebola has wreaked havoc on the populations and health care systems of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and it’s also completely disrupted agriculture production and distribution, Juan Lubroth, the FAO’s chief veterinary officer, told POLITICO.

In the countries’ efforts to block the movements of people to limit the spread of the disease, governments have set up roadblocks and limited traffic, a strategy that has also isolated and shut down farming operations, he said.

“The land has not been tilled to plant,” he said. “So we’ve missed several aspects of the planting season for crops over the last several months. The next crop will not be ready. We won’t have one and we see a food crisis already.”

© 2014 POLITICO LLC